An Interview with Brett Joseph

B rett Joseph is an organizational systems consultant, researcher and educator. He directs the non-profit Center for Ecological Culture and the Cleveland Educator’s for Sustainability, teaches permaculture at Lorain County Community College, Ohio, and is a member of the Great Lakes Biomimicry Collaborative. His consulting practice builds on his 20 years of experience as an environmental attorney, organic farmer and community organizer. A current Ph.D. student in Organizational Systems at Saybrook University, Brett has professional and master’s degrees in law and an MA in humanistic and transpersonal psychology. He also has certificates in civil mediation, socially-engaged spirituality, permaculture design, green building and environmental education. Brett’s published writings focus on innovation, culture and whole systems approaches to fostering human and ecological health.

rett Joseph is an organizational systems consultant, researcher and educator. He directs the non-profit Center for Ecological Culture and the Cleveland Educator’s for Sustainability, teaches permaculture at Lorain County Community College, Ohio, and is a member of the Great Lakes Biomimicry Collaborative. His consulting practice builds on his 20 years of experience as an environmental attorney, organic farmer and community organizer. A current Ph.D. student in Organizational Systems at Saybrook University, Brett has professional and master’s degrees in law and an MA in humanistic and transpersonal psychology. He also has certificates in civil mediation, socially-engaged spirituality, permaculture design, green building and environmental education. Brett’s published writings focus on innovation, culture and whole systems approaches to fostering human and ecological health.

What are your impressions of the current state of biomimicry/bio-inspired design?

At present, biomimicry appears to be emerging as a “new” academic discipline and specialized area of professional practice within a variety of institutional settings. However, my impression is that the implications of biomimicry, as a paradigm shift in the way we understands the relationship between Nature and human society, are far from being realized. For this shift to occur in a manner that fulfills biomimicry’s transformative potential, biomimetic scholars and practitioners must give voice to a transformed consciousness that critically deconstructs and transcends the “separation consciousness” still prevails as the modern worldview.

Biomimicry professionals must adopt the vision, language and habits of a holistic, integral consciousness that builds on the social and technological advances of the preceding era, while actively revisioning our most fundamental conceptions regarding Nature and its meaning in our lives. I believe biomimicry professionals have an opportunity and responsibility to foster deep learning among colleagues, clients, students and others who are interested in their work; to facilitate a massive shift in consciousness that is essential if global crisis is to be averted. In this way, biomimicry, with its emphasis on practical design solutions, has the potential to serve as a “bridge between worldviews,” constructed by those who are well positioned to elaborate on life’s principles and articulate how these principles can be applied to various human activity systems. Because biomimicry in practice can yield elegant and sustainable design solutions to all manner of technological, environmental and social problems, it has the potential to garner a wide audience and become the basis for rapid diffusion of innovation that allows society to adapt to changing conditions while accomplishing a transition to a sustainable economy.

Biomimicry professionals must adopt the vision, language and habits of a holistic, integral consciousness that builds on the social and technological advances of the preceding era, while actively revisioning our most fundamental conceptions regarding Nature and its meaning in our lives. I believe biomimicry professionals have an opportunity and responsibility to foster deep learning among colleagues, clients, students and others who are interested in their work; to facilitate a massive shift in consciousness that is essential if global crisis is to be averted. In this way, biomimicry, with its emphasis on practical design solutions, has the potential to serve as a “bridge between worldviews,” constructed by those who are well positioned to elaborate on life’s principles and articulate how these principles can be applied to various human activity systems. Because biomimicry in practice can yield elegant and sustainable design solutions to all manner of technological, environmental and social problems, it has the potential to garner a wide audience and become the basis for rapid diffusion of innovation that allows society to adapt to changing conditions while accomplishing a transition to a sustainable economy.

My related concern is that professionals who advance biomimicry as a distinct discipline or specialty must not allow their interests in personal career development to create the impression that biomimicry is something esoteric; just another professional specialization that is the exclusive domain of experts within the compartmentalized framework that is reflected in so many of today’s academic departments and R&D institutions. Biomimicry professionals must be prepared to acknowledge and celebrate biomimetic design thinking and applications across a wide spectrum of activities, including areas of practice where the term “biomimicry” is not currently being used. This is possible only if practitioners remain committed to an ongoing, interdiscipinary dialogue regarding the core ethics, principles and design methods of biomimicry that can be found in examples worldwide, including many practices found in traditional cultures. We must open new lines of communication, among lay, academic and professional practitioners. Finally, the further elaboration of biomimetic thinking across disciplines must involve a corresponding exploration of human and natural systems that is place-based, continuously evolving and legitimized through broad stakeholder participation.

What do you see as the biggest challenges?

I think there are several big challenges. First, even though biomimicry offers solutions relevant to all sectors of society, access to opportunities for direct observation of the world’s natural ecosystems is more limited. Those with access (e.g., the ability to travel to and enter into remote natural areas) including those with lab facilities and technological “extensions” such as microcopes that allow for observation at the nano-scale, may be looking for solutions to particular problems other than those that concern many who do not have access. Therefore we face the challenge of observing and cataloguing information relevant to biomimetic design in a manner that is broadly accessible (presumably on an open source basis) and not overly constrained by specific research agendas or the categories or measurements we use to organize the information obtained. As we know from the field of quantum physics, the observer is not a neutral or passive part of the system observed. Therefore, the process of “how” we go about “asking nature” can have major implications for the answers we receive. Yet, even the phrase “ask nature” implies a continuation of separation consciousness, with nature conceptualized as “other.” I believe that along with the challenge of transforming consciousness and ways of knowing, the process of observation and interpretation of “nature’s solutions” must be allowed to evolve along with the cultural biases and learned perspectives that color the way we see nature and natural systems.

Second, more work needs to be done in the area of developing research methodology that is well adapted to biomimetic design. We are challenged to convince the scientific community at large that design thinking is a legitimate form of disciplined inquiry and that “right brain” methods of inquiry such as pattern recognition and reference to the self-organizing characteristics of natural systems are valid sources of knowledge that should carry the weight of scientific legitimacy. I am not convinced that it is wise at this juncture to play up the distinction between “science” and “design”, as if the two modes of thinking are in competition with each other for being considered the most valid sources of “real world” solutions. There is a long history embedded in western culture that privileges a mechanistic view of nature that is in many ways antithetical to biomimetic thinking. To address this challenge, we might explore how design thinking can be taught and understood as a form of disciplined inquiry that is grounded in systems thinking and overcomes the severe limitations of the traditional scientific epistemology.

In addressing this latter challenge, we also must maintain an ethical stance that consistently emphasizes relationships of exchange and mutual benefit as we interact with other species, and that guides scientific inquiry with a view to maximizing social and ecological benefit. In other words, biomimicry should be well grounded in bioethics, and learning from nature should always be pursued with humility and a deep appreciation for Nature’s complexity. Learning to participate by “asking Nature” should never be allowed to devolve into just another attempt to “play God”. Our culture has a long history of scientific discoveries being misapplied in harmful ways under the rationale of scientific “objectivity.” Biomimicry should take a stance that is nature-centered, and that views all human activity as a co-creative part of the natural systems that are in and around us.

What areas should we be focusing on to advance the field of biomimicry?

As mentioned above, we need to focus on the areas that are most challenging to our familiar mindset of separation consciousness. Janine Benyus sets the tone by the way she infuses her speech and writing with a deep appreciation for the design wisdom of Nature, coming from a place of participatory, even transpersonal, consciousness. The power of biomimicry lies in the interdisciplinary dialogue it engenders, between artists, engineers, business managers, social scientists, theoreticians, ethicists, architects, and many others. We must focus on the process of dialogue itself, and develop ways to consciously evolve ourselves and our language so as to optimize the value of our diversity and utilize the breadth of our collective expertise.

How have you developed your interest in biomimicry/bio-inspired design?

I have chosen to focus as much on the “inner landscape” as on the “outer landscape” and, especially the relationship between the two, i.e., how our natural and cultural surroundings shape our thoughts and perceptions of world, and how the patterns that we create in our built environments, in turn, express the evolution of our culture and our ways for relating to the rest of life.

What is your best definition of what we do?

We are building individual, organizational and network-level capacities for innovation that is inspired by design solutions observed in Nature; enabling processes of transformative learning and interdisciplinary collaboration that foster cultural evolution on a trajectory that optimizes the alignment between human culture and the natural systems upon which we depend.

By what criteria should we judge the work?

By what criteria should we judge the work?

I believe we should adopt a “nature-centered perspective” that judges our work according to the “prime directive” of whether our work and our human interventions in natural systems tend to promote conditions favorable to life, and evolutionary change in nature and society towards higher levels of complexity; including natural tendencies towards increasing diversity and increasing integration. Our agenda should be to restore the health and resilience of local communities and ecosystems, while creating conditions favorable to the long term well-being and quality of life of ourselves and our fellow life forms, those who share with us the abundant, yet limited resources of our home planet Earth.

What are you working on right now?

As a teacher of permaculture design, I am developing and teaching curriculum that explores biomimicry and permaculture as two complementary “mimetic” systems of inquiry and practice. As an organizational consultant I founded the Center for Ecological Culture, Inc. with a mission to facilitate the development, transformation and strengthening of organizational systems that sustain value-driven innovation and exhibit the integrity and resilience of healthy natural ecosystems. As a Ph.D. student in organizational systems, I am currently engaged in action research that explores how community-based inquiry groups using an evolutionary learning systems methodology can transform the way we organize ourselves to solve complex problems in society and the human environment. I will be presenting a paper on this topic at the June Biomimicry Educators conference. Finally, as educational consultant, I am working with teachers and other stakeholders in the Cleveland area K-12 system(s) to bring sustainability education, and biomimicry in particular, into the classroom.

How did you get started in biomimicry/bio-inspired design?

I was introduced to biomimicry back in 2008 while preparing to teach a permaculture workshop at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. I found a copy of Janine Benyus’ book in the museum bookstore and read it with great interest. After returning to school to pursue my Ph.D. in organizational systems, I began to explore the implications of biomimicry as an approach to the design of learning communities at the inter-organizational network level. My emerging knowledge of biomimicry further informed my thinking as founder of the Center for Ecological Culture, a non-profit organization dedicated to organizational development that aligns with the qualities of healthy natural ecosystems. About a year ago, I received an invitation via a local organization, the Corporate Sustainability Network, to participate in a two-day biomimicry symposium organized by the newly formed Great Lakes Biomimicry Collaborative. This event put me in touch with numerous other professionals from northeast Ohio and beyond who share a common interest in the development of our region as a hub of research and innovation based on biomimetic design thinking and its many applications.

Which work/image have you seen recently that really excited you?

I am most excited about the work of a German organization, the Institute for Participatory Design, and their research, authored by Jascha Rohr & Sonja Hörster (2011) using a “field process model” as a theoretical framework for understanding generative design as a process of dynamic interactions of forces in a field. Their model can serve as a useful guide to the facilitation of transformative learning in groups, by positing a conceptual linkage between processes of ‘immergence” that, in biomimetic terms, can be compared to tree sending its roots deep into the soil, and processes of “emergence” that is the flourishing of creativity and innovation akin to the upward branching of the tree as it reaches for the nourishing light of the sun. The basic pattern bears close resemblance to the General Core Model developed by Bill Mollison, co-founder of permaculture, which describes a metapattern (pattern containing many other embedded patterns) found throughout Nature and appearing as the image of an “apple core.” This all may seem very abstract, but I was excited to encounter a model that allowed me to see in Nature a universal pattern that helped me visualize the transformative learning processes in organizations, which involves inward (deepening) and outward (extending) dimensions of inquiry.

What is your favorite biomimetic work of all time?

I was most inspired by the work of renown naturalist and wilderness tracker Tom Brown, who reintroduced my generation to deep learning and nature awareness that is rooted in native american and other indigenous cultures, and that provides an accessible pathway for postmoderns such as myself to reconnect with the larger life world that is all around us. Subsequent work by author Jon Young in the area of cultural mentoring was inspired by the teachings of Tom Brown and carries on a lineage of nature wisdom that is deeply rooted in the psyche and land of North America.

What is the last book you enjoyed?

Restoration agriculture: Real-world permaculture for farmers, by Mark Shepard (2013).

Who do you admire? Why…

Who do you admire? Why…

I always wanted to be Jacques Cousteau, whose films introduced the world to the “exhuberant” life below the ocean waves, and who embodied the spirit of explorer, artist, inventor, futurist, and global citizen. He was the only individual who was not a head of state to serve as a formal delegate at the Earth Summit in Rio, 1992.

What’s your favorite motto or quotation?

“If you're going to follow your bliss you're going to follow your blisters.

Sometimes the road gets rocky.

Sometimes the obstacle is in the way and sometimes the obstacle is the way.”

Michael Meade, mythologist, author and founder of the Mosaic Multicultural Foundation

What is your idea of perfect happiness?

What is your idea of perfect happiness?

Standing on the seashore in the presence of loved ones, watching the gulls ride the thermals of a light onshore breeze, while sand fills the gaps between my toes and foam wraps around my bare ankles.

If not a scientist/designer/educator, who/what would you be?

A film-maker, definitely. Perhaps in my next life!

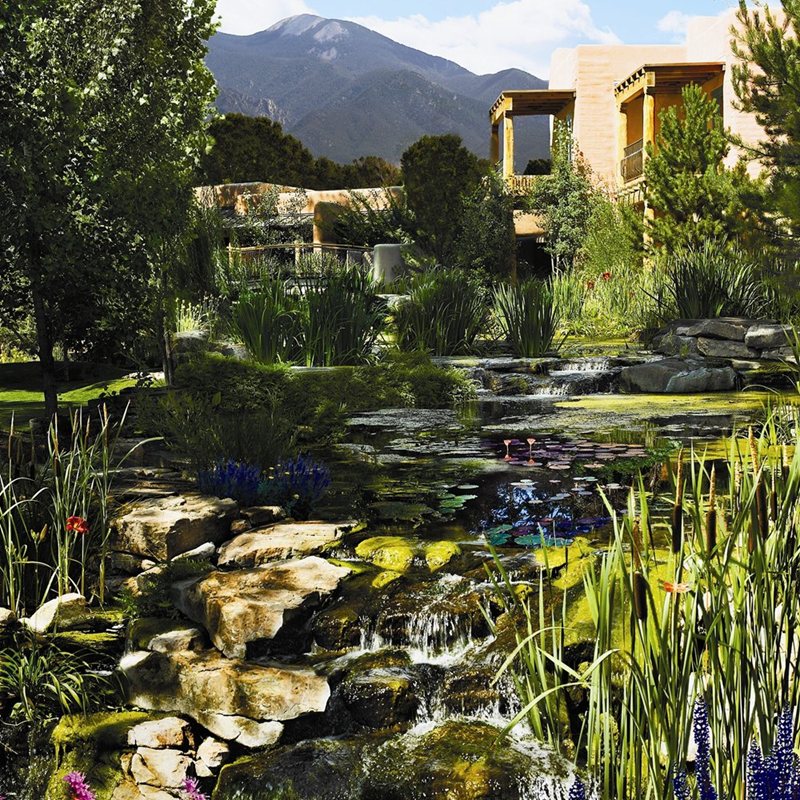

Image Credits:

- On Air: © frank peters - Fotolia.com

- Totem Pole: © serjiob74 - Fotolia.com

- El Monte Sagrado Resort: Living Machines

- Hawksbill Turtle and Scuba Divers: © Richard Carey - Fotolia.com