The Evolutionary Basis for the Chemical Defense of Bombardier Beetles (Kathryn Nagel, Marc Weissburg)

Complex biological designs are often used by proponents of intelligent design as evidence to refute evolution. In their view, the idea that organisms perform functions necessary for their survival (i.e., are “designed” for certain tasks) is taken as evidence for the existence of a designer. Those who do not accept the scientific validity of evolution appear to be fixated on the use of the word “design”, which in their view must represent an intentional process. As is clear from hundreds of years of study across many fields, evolution is a design process that is sufficient to account for biological characteristics without requiring a guiding intelligence.

Complex biological designs are often used by proponents of intelligent design as evidence to refute evolution. In their view, the idea that organisms perform functions necessary for their survival (i.e., are “designed” for certain tasks) is taken as evidence for the existence of a designer. Those who do not accept the scientific validity of evolution appear to be fixated on the use of the word “design”, which in their view must represent an intentional process. As is clear from hundreds of years of study across many fields, evolution is a design process that is sufficient to account for biological characteristics without requiring a guiding intelligence.

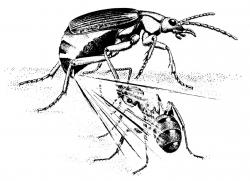

Bombardier beetles have a highly sophisticated chemical defense system that emits a heated fluid at high pressure and has been used as an inspiration for manufacturing technology (see Swedish Biomimetics 3000® article in the February 2008 newsletter. Although proponents of intelligent design argue that the complex and specific anatomical structures and chemical secretions provide proof of intentional design, the scientific evidence relating to the chemistry of the spray, the evolutionary history of anatomical characteristics and the limitations of the defense system reveals a clear evolutionary process.

When disturbed, some bombardier beetle species can emit rapid pulses of superheated chemical spray from their abdomen that can be accurately aimed in any direction, effectively deterring both vertebrate and invertebrate predators. Proponents of intelligent design argue that all of the components of this system must evolve simultaneously - piecemeal evolution through a series of stages results in animal properties that would not be adaptive and may even be harmful. They argue that without the elaborate structures to control and direct the spray, the chemical reaction would cause the beetle’s abdomen to explode. However, thermodynamic analysis of the reaction confirms that the chemical components do not cause an explosive reaction, but rather it is the high pressure maintained in the outer chamber that results in high temperatures. The release of the hot fluid is the result of a pressure build-up (much like the valves in mammalian hearts) and occurs before the internal pressure reaches levels dangerous to the beetle.

When disturbed, some bombardier beetle species can emit rapid pulses of superheated chemical spray from their abdomen that can be accurately aimed in any direction, effectively deterring both vertebrate and invertebrate predators. Proponents of intelligent design argue that all of the components of this system must evolve simultaneously - piecemeal evolution through a series of stages results in animal properties that would not be adaptive and may even be harmful. They argue that without the elaborate structures to control and direct the spray, the chemical reaction would cause the beetle’s abdomen to explode. However, thermodynamic analysis of the reaction confirms that the chemical components do not cause an explosive reaction, but rather it is the high pressure maintained in the outer chamber that results in high temperatures. The release of the hot fluid is the result of a pressure build-up (much like the valves in mammalian hearts) and occurs before the internal pressure reaches levels dangerous to the beetle.

Studies across bombardier beetle species show a clear pathway whereby the sophisticated spray defense mechanism evolved in stages, each of which is useful in its own right and therefore provides an evolutionary advantage. Bombardier beetles comprise two different evolutionary branches within the family Carabidae. Species in the primitive (paussoid) branch do not have an advanced spray mechanism but instead use grooves on the sides of the abdomen to direct their chemical defenses in the general direction of predators. The most primitive bombardier species M. contractus has rudimentary glands with two chambers that secrete quinones in a bubbling froth rather than a directed spray. This demonstrates that the advanced mechanism of a directed spray has evolved in incremental stages, each providing evolutionary benefit.

The intelligent design argument that novel complex structures cannot evolve in stages also questions how the evolutionary process could account for the specific chemical components involved in the defensive spray. This argument ignores the widespread use of these chemicals in other life-processes. In fact, evolutionary steps from the basic storage of quinones to the intense jet-like pulses can be identified. Quinones are produced by many different insects and the most primitive use of them is storage in the skin, since quinones are quite foul tasting. Related insects have evolved structures to house and store these chemicals. Since chemical defenses evolved in the Carabidae family as early as 100 million years ago, these insects have had a long time to evolve from primitive storage and secretion mechanisms to complex sprays of superheated quinones, from the abdominal grooves in primitive families to the complex spray-aiming tip in the advanced beetles. Phylogenetic data supports the evolutionary lineage and the increase in complexity of the spray mechanism over time.

The final argument for the preeminence of evolution in the production the spray-defense mechanism of the bombardier beetle relates topredator-prey interactions. Bombardier beetles are able to successfully avoid predation by many different types of predators. However, even the elaborate spray-defense mechanism is not designed so perfectly that it deters all predators. One species of orb weaving spider, Argiope, is able to capture the bombardier beetle using a patient and careful strategy. When first caught in the web, Argiope advances towards the beetle and throw silk around it without attempting to seize the beetle, eventually covering the beetle with silk and hampering its chemical spray. Certain bird species may also be able to avoid the harsh chemical defense of the bombardier. In other words, predation is still a driving force and the unconscious evolutionary process still continues to influence this system as environmental conditions change.

The three-pronged examination of the chemical basis of defense, the progression of defensive structures within the beetle’s evolutionary lineage and the driving forces behind bombardier beetle evolution reveals many distinctive aspects of this beetle and its interaction with other species. By focusing on the final form, supporters of intelligent design often overlook and rarely consider the rich history of the bombardier beetle’s defense system. While more study of bombardier beetles is required, established literature supports the evolutionary explanation for the defense mechanism of these complex and extraordinary insects.

Suggested Readings

- Bergman, Jerry. Can evolution produce new organs or structures? (2005) Journal of Creation. 19(2): 76-82.

- Conner, William E.; Alley, Kerensa M.; Barry, Jonathan R. and Harper, Amanda E. Has vertebrate chemesthesis been a selective agent in the evolution of arthropod chemical defenses? Biol. Bull. (2007) 213:267-273.

- Dean, Jeffrey; Aneshansley, Daniel J.; Edgerton, Harold E.; Eisner, Thomas. Defensive spray of the bombardier beetle: A biological pulse jet. Science. (1990) 248: 1219-1221.

- Dettner, Konrad. Chemosystematics and evolution of beetle chemical defense. Ann. Rev. Entomol. (1987) 32: 17-48.

- Eisner, Thomas et al. Effect of bombardier beetle spray on a wolf spider: repellency and leg autotomy. Chemoecology (2006) 16(4): 185-189.

- Eisner, Thomas et al. Spray mechanism of the most primitive bombardier beetle (Metrius contractus). Journal of Experimental Biology. (2000) 203: 1265-1275.

- Eisner, Thomas and Aneshansley, Daniel J. Spray aiming in the bombardier beetle: Photographic evidence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. (1999) 96: 9705-9709.

- Eisner, Thomas and Dean, Jeffrey. Ploy and counterploy in predator-prey interactions: Orb-weaving spider versus bombardier beetles. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. (1976) 73(4): 1365-1367.

- Maddison, David R.; Baker, Michael D. and Ober, Karen A. Phylogeny of carabid beetles as inferred from 18s ribosomal DNA (Coleoptera: Carabidae). Systematic Entomology. (1999). 24:103-138.

- Morrison, Joan L.; Abrams, Jeffrey; Deyrup, Mark; Eisner, Thomas and McMillian, Michael. Noxious menu: chemically protected insects in the diet of Caracara cheriway (Northern Crested Caracara). Southeastern Naturalist. (2007) 6: 1-14.

- Poinar, G.O.; Marshall, C. J. and Buckley, R. One hundred million years of chemical warfare by insects. Journal of Chemical Ecology. (2007) 33:1663-1669.

- Roth, L. M. and Eisner. T. Chemical defenses of arthropods. Annual Review of Entomology. (1962) 107-136.

- Skelhorn, John and Ruxton, Graeme. Ecological factors influencing the evolution of insects’ chemical defenses. Behavioral Ecology (2007).

(Photos provided by Professor Andy McIntosh, University of Leeds.)

Kathryn Nagel is a lab technician and researcher in the School of Biology at Georgia Tech.

She primarily studies the affect of harmful algal blooms on copepod behavior and chemical signaling.

Implications of Evolution to the BID Process

Designers who wish to utilize BID effectively must be cognizant of evolution. As the accompanying piece by Kathryn Nagel makes clear, the design process responsible for properties of biological systems (i.e., evolution) is rather different from the (hopefully!) intentional process of a human designer. Although we often use the terms biological solutions, we are nonetheless referring a set of properties that achieve a given function as a result of evolution, not deliberate design.

In addition to lacking conscious intent, the evolutionary design process capitalizes on preexisting structures or properties, sometimes creating new functions that are wholly unrelated to previous usage. The evolutionary process has been likened to tinkering; many unsuccessful modifications are created, and the most successful new variants go forward. These changes occur within a group of organisms that are related by descent, and new properties are the result of modifications to earlier characteristics. The ways in which biological systems achieve functions therefore are strongly constrained by history. Although serious students of design may recognize that some of these problems plague our design process as well, we can choose to avoid these constraints. Such options may challenge us, but are virtually impossible for the evolutionary design process.

Teaching BID to many different groups has lead us to conclude that a basic understanding of the evolutionary process leads to more effective strategies for researching potential biological solutions. Many designers lack this appreciation, or are unable to translate their understanding of the evolutionary process into search heuristics. We present a short list of how to search biological systems productively given the constraints of the evolutionary design process.

- Biological functions evolve in response to a challenge faced by organisms. Some human problems may have no direct analog to ones that confront organisms.

- Evolution is “satisficing” rather than optimizing. A given solution need only be better than the existing one - it may not be the best solution. Searching broadly and understanding the principle (instead of simply copying an existing solution) generally is advisable.

-

Solutions may be shared simply because animals are related, not because a given solution is the only one. Searching broadly is required to establish both the generality and robustness of a given biological solution.

Marc Weissburg is a founder and co-director of the Center for Biologically Inspired Design

at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Comments

Bombardier Beetle spray mechanism

Kathryn / Marc - Just a word on your article in the latest BIDS newsletter. I don’t think the article on the bombardier beetle got the mechanism used by the beetle correct. I explained some of this in the lecture I gave to the BIDS Centre at Georgia 2 years ago (Sept 2008).

The statement "However, thermodynamic analysis of the reaction confirms that the chemical components do not cause an explosive reaction, but rather it is the high pressure maintained in the outer chamber that results in high temperatures” is not true. The heat does come from the chemical reactions as explained by Schildneckt and analysed by Eisner, Aneshansley and co-workers (see refs below). Our group at Leeds go into this with a number of papers that we have produced which explain this further. The heat is not primarily generated by pressure. The Physics World article we wrote (see below April 2008) is perhaps a summary you might find helpful in explaining the principle being used by the beetle system. The chemistry does indeed instigate the explosion through the catalysts catalase and peroxidase accelerating the production of hydrogen from the hydroquinone which then combines with the oxygen from the hydrogen peroxide. Though the full explanation of the production of these reactants is not yet fully understood in the beetle, the thermodynamics of the heat production in the chamber is such that the overall heat release is approx -202.8 J/mol and the heat content of the reservoir solution is found to be approx 0.8 J per milligram of the solution. There is then an inlet pinch valve and an outlet pressure relief valve system which controls the hot exhaust of the steam, the shattered water droplets and the toxic quinone mixture. It was the discovery of the outlet valve in 2005 from Tom Eisner's SEM photographs which was the key to finally unlocking the principle concerning how the beetle exhaust system worked.

You can read more in the references below which give some detail of how the principle of the ejection system works, as well as more detail on the chemical heating and enthalpies of combustion :

Schildknecht, H. and Holoubek, K. (1961) Angew. Chem. 73 1–7

Aneshansley, D. J., Eisner, T., Widom, M. and Widom, B. (1969) Biochemistry at 100 ◦C: explosive secretory discharge of bombardier beetles (brachinus) Science 165 61–3

Beheshti, N. and McIntosh, A.C. (2007) “A biomimetic study of the explosive discharge of the Bombardier Beetle.” Int. J. of Design & Nature, 1(1), pp.61-69.

McIntosh, A.C., Combustion, fire, and explosion in nature - some biomimetic possibilities. Proc. IMechE, Part C: Journal of Mechanical Engineering Science, 221(C10), 1157–1164, 2007

Beheshti, N. and McIntosh, A.C. “The bombardier beetle and its use of a pressure relief valve system to deliver a periodic pulsed spray” Bioinspiration and Biomimetics (Inst of Physics), 2, pp.57-64, 2007.

McIntosh, A.C. and Beheshti, N, “Insect inspiration”, Physics World (Inst of Physics), 21(4), 29-31, April 2008.

For any further discussion, you are welcome to email me - please go through Norbert Hoeller, the editor, to make contact.

With regards,

Andy McIntosh (Leeds)

Marc Weissburg

Thanks Andy-I had completely forgotten you covered this. I will take a look and try describe this more accurately.

cheers

Marc W

The joy of scinece

This is what I love about science: we can "argue" about the science just by dealing with the facts. I hope I read this correctly, that whether it's pressure or chemistry that causes the explosive reaction, the science negates the notion of ID. Unfortunately, many lay folks confuse such scientific discussions with some kind of substantive inconsistency in the science itself.

Cheers.

Fil

Yes, but design isn't intentional

As a staunch anti-theist, I am grateful for the level-headed and detailed examination provided in this article. It is quite clear that those who advocate for ID have not a clue of what evolution really is. I also agree that an understanding of evolution is pretty much a prerequisite for any practicing designer with aspirations to execute BID.

But I do not agree with the description of designing as a process that can happen without intent. This is simply a matter of lexicography, and not science, but it is important nonetheless because a lack of precision in the use of language can be as harmful as a lack of precision in doing science. In the history of the word "design," there has always been a connotation of intent. We do things "by design" or "by accident."

Thus I would urge the authors to reconsider their position on the use of "design" to describe how evolution works. ID proponents believe in intent behind evolution. There is no evidence of intent. Therefore there is no design.

This changes how we view the implications for BID practitioners. We cannot substitute a design process for an evolutionary one, and vice versa. However, we can use a knowledge of how evolution works to learn how to understand situations for which designed solutions are desired.

One project I am involved with is the development of a perspective on the role that design plays in the larger systems of society. Consider this "loop:" designers design things that are made and put into use. If those products are "successful," then those products become more plentiful - just as successful organisms grow in number. Over successive generations of products, aspects of successful products can pass into other products - a kind of cross-breeding. Occasionally, mutations can occur - not that a product spontaneously changes, but rather that a new use for an existent product is found not by the designers, but by the users. iPods being used by medical workers as data transfer devices is an example. These kinds of new uses were part of Apple's stimulation to move toward devices that were information stores and manipulators (iPod Touch, iPhone, iPad).

This "big loop" - where designers react to the success of extant products - can be thought of as a kind of evolution, exactly because in this case there is no intent.

Nonetheless, I certainly appreciate this article for all its other substantive merits.

Cheers.

Fil

Implications of Intention in Design

Fil, I would like to explore the implications of intent in design further - I think it may be relevant both to identifying situations where BID is appropriate and also affecting how well designers take to BID, particularly if they are concerned about bio-inspiration constraining their creativity.

Intent in the sense of being able to plan requires considerable intelligence and possibly self-consciousness. Our vast knowledge and foresight clearly give us advantages over natural selection. As Marc pointed out, natural selection is heavily constrained and change occurs at a relatively slow pace, although there is growing evidence that it can occur quickly in some circumstances. Kauffman argues in The Origins of Order: Self-Organization and Selection in Evolution that the immune system is able to rapidly evolve new antibodies against novel antigens in a matter of days.

Are there different degrees of intent in design? Alexander in Notes on the Synthesis of Form distinguished between unconscious (problem-driven, conservative) and conscious (creativity-driven, progressive) design and argued that many of our design missteps are due to an excessive focus on the latter. Many of the environmental issues we are facing are at least partly caused by our technological strength. This suggests design should give greater importance to the specific context of the problem and how the problem/solution fits within the encompassing systems. Your idea of 'design as balancing' seems consistent with this approach. Limits might even be useful in stimulating effective innovation. David Oakey, designer of the Interface Entropy carpet tile, believes abiding by the principle of diversity created ongoing opportunities for his designers (page 9 of the December 2005 Newsletter), while Julian Vincent proposed to a group of philosophers that the greatest barrier to creativity was the blank page.

What is the operational impact of 'intent' in design? Do some of differences between intentional and unintentional design disappear at larger scales? The designer could be seen as an agent introducing change through novelty (mutation) and making new connections (re-combination). As you point out, forces outside of the control of the designer ultimately determine which changes survive. What contribution does intent make in the greater scheme of creating designs that are successful over the long haul?

Norbert, Alright-y

Norbert,

Alright-y then!

Planning is something that some animals can do (planning is a part of problem solving), so there must be a spectrum of planning capability. Planning the sorts of things that humans do does require considerable intelligence. I'd say self-consciousness is also required because you can plan things for your self, so you must have a self-image and the ability to reason about that model of yourself - which is pretty much what self-consciousness is.

Since natural selection has been running along swimmingly for several aeons, but we humans are on the verge of screwing the pooch after only a few thousand years of "advanced" capabilities, I have to wonder if "Our vast knowledge and foresight clearly give us advantages over natural selection." is less than accurate.

I think evolution can happen quickly, so long as the evolving organism can adapt to changes fast enough. I also think simple organisms can adapt faster than complex ones. I've read of several cases of natural selection happening in hours (in a petri dish); all those cases were, like, strands of DNA, or single-cell organisms. Needless to say, humans can't evolve in a day. Or at least, they haven't yet, so I'll play the odds and say they won't.

If there's a range of planning capabilities, and planning is needed for intent, then it follows that there's also a range of intentional capabilities.

I'm not sure Alexander wrote about self-conscious vs unself-conscious design. He did write about self-conscious and unself-conscious cultures. My reading of NSF was more like: there's people who intend to design (which means they know what design is and have some idea of how to do it), versus people who do designerly activities without knowing they're doing design. I do agree that Alexander sees many of today's problems arising from too much self-consciousness on design rather than on the problem/situation that design activities are supposed to solve/balance. And I think he's right about that.

That's exactly what designing as balancing is supposed to be for.

Of course, creativity works best under constraint. Creativity is a response to some stimulus. The "blank page" is the ultimate lack of stimulus.

Part of the impact of intent in design is, I think, that designerly people actively seek out, or perhaps just have a natural ability to perceive, the boundaries (constraints) of situations, which in turn drives the creative bits. Not that designing is only creating.

There's a difference between intending to design, and intending to carry out designerly activities - by this I mean that some people intend to, using my language, balance a situation they find undesirable. There's intent, but not intent to design. Someone like me, on the other hand, intends both to balance some situation and to use design to do it. The difference is that, by knowing what designing is, I would intentionally use knowledge of design methods to solve the problem or balance the situation. If I don't know what design is, then I can't intend to do it.

I think intention disappears at the large scale, if I understand the question, because the intent is not externalized. Only the results of the actions taken to fulfil the intent are externalized. Being a total computer geek, I like to think of it in terms of object-oriented programming. Intention is "encapsulated" within the agent/object. One could substitute any other agent, with or without the ability to intend; so long as its externally visible behaviours and functions are the same, no external system will notice the difference.

At this larger scale, I don't think intent matters at all. However, I also think that we have nothing else on which to base our behaviours besides intent. I mean, if I were to stop intending to do things, what could I substitute for intent that would satisfy its role in my psyche? I know of nothing, but I'll entertain suggestions. :)

I think the real issue of intent is what we really intend to do. Companies intend to "increase shareholder value" - sustainable products are only a means to achieve that end. Many designers really intend to express their own creativity because it brings them pleasure or some pleasurable by-product (fame, wealth, glory, chicks, a gold-plated Hummer, ...whatever). I myself have no delusions of my own work: in the end, everything I do from teaching to writing this comment now, I do because I derive pleasure from it in some way.

I've often called design a "service." We design for others (and maybe ourselves, but only in addition to others). If you really intend to do something for others, then the way to maximize your personal pleasure from the act is to focus on the situation that needs balancing, the problem that needs solving, and not the application of a pet method or anything like that.

I don't know if this is coming out right, but it's the best I've got right now.

Cheers.

Fil

Implications for Designers

Fil, you raise important points about how designers think and work. Although some (particularly in architecture) have 'taken' to bio-inspired design, my sense is that many may perceive BID as constraining. Benyus talks of "quieting human cleverness" and that "most of our challenges have already been solved". On the surface, this seems contrary to the very essence of design.

On the other hand, "Quieting: Immerse ourselves in nature" in Biomimicry (Benyus, 1997, p. 287, ) promotes an openness to new possibilities and an awareness of our place, not as an insignificant dot in universe but as an active participant in a history that extends for billions of years. Rather than limiting designers, we are expanding their palette and emphasizing the critical importance of their work. I suspect most designers would be motivated by the possibility that their efforts could have a positive impact on the challenges facing humanity.

Much as we would like designers to work 'with' nature, I think we need to make bio-inspiration work 'with' designers. Goel's work on cognition is a key component. Giving designers meaningful challenges is another. What intrigued me about the Ecological Performance Standards that were mentioned in Perspectives on the HOK/Biomimicry Guild Partnership is the opportunity to raise the bar (encourage designers to develop solutions that product comparable outcomes to natural systems) while at the same time providing information on how these natural systems function. To me, that connects directly to what motivates designers.

single words are not always sufficient

I think I understand your thoughts, but I am not ready to ceede the use of the word "design". We all understand that design means something about function, and this is important enough a link between human and biological approaches to, at least to me, justify the use of this word. It is a very powerful bridge between fields that facilitates communication. I do think it is fair and accurate to speak of an evolutionary design process as one that results in the achievement of function without intent, which is more or less what we are trying to say. As you mention, there are important similarities between the process in both human and biological worlds. As long as we specify a lack of intent-I don't think we are describing the process falsely. Given the caveat-I am not able to come up with a more parsimonious and accurate phrasing.

thanks for the comment

Marc

Okay

Design is just a word; what really matters is what we mean by it. We could call it Fred; it wouldn't change the underlying concept. So given that we seem to agree with the lack of intent, then I'm good.

Cheers.

Fil